Exploring Patagonia’s Ice Fields by Packraft

Story, photos & maps by Waldo Aguayo. Read Waldo’s story, “San Quintin Chilean Expedition.”

Prologue

Lizzy Scully, owner of Four Corners Guide, asked me to write an article about my latest Patagonia packraft expedition. Writing articles for her has helped me clarify my thoughts and visions of life.

She wanted more than I offered in my first draft, which was just a trip report, which she says are boring. “Please tell me more about why this kind of trip motivates you,” she asked… “Because it’s the unknown? Because the places you go are beautiful? Because it looked difficult? Why?”

What she didn’t know is that I ask these myself and others these questions all the time. So I dug deeper. What motivates me to go on big Patagonia packraft expeditions? Why invest all my energy and time in these outdoor excursions, living far from my family, sometimes being cold, hungry or afraid? Do I like the feeling that I am fragile and tiny in the lands I am visiting? Well, yeah… to all those things.

As Many patagonia packraft expeditions As Possible!

In these modern times, we don’t explore for the same reasons we explored hundreds of years ago. Humans have always sought to reach different places. But nowadays why? Is it for personal ego? To be able to publish only the successes in social media? Or is it to stand out among modern explorers, mountaineers, kayakers, packrafters?

A few years ago, when I started paddling packrafts, I found new opportunities to traverse on my maps. I have always liked looking at maps, especially since I came to live in Patagonia and the Aysen Region. And I’ve been a dreamer since childhood. While in high school playing basketball, I dreamed of being a professional player. When studying Adventure Tourism in college, I practiced rock climbing and bouldering for a couple of years, and dreamed of going on a climbing trip with my friends.

And Now I’m a Packrafting Guide!

And now as a paddler and packrafting guide at Laguna San Rafael, the story is the same. The San Rafael Glacier is the second largest glacier in Campo Hielo Norte. I studied a lot about it and its geography, flora and fauna, history and above all the expeditions and explorations that have been done in the area. And I even discovered some routes people had done in packrafts. This inspired me to want to explore as many of the Northern Ice Field glaciers as possible via packraft. So far I’ve seen a dozen. And what I saw as a dream a few years ago has become a reality I might even achieve in my lifetime.

My latest mission is just one more piece of that puzzle that I have tucked neatly into place.

exploring The NOrthern Ice fields

Patagonia is known worldwide as a place with a unique geography and culture. As a Chilean, I feel really lucky to live here and regularly embark on Patagonia packraft expeditions. On our side of the mountains (Argentina is on the other side) lie the largest ice masses in the southern hemisphere, outside of Antarctica. One of these is the Northern Ice Field, located entirely in the Aysén del General Carlos Ibáñez del Campo Region, where I live. From North to South the Northern Ice Field is about 120 km long. And from East to West it’s between 50 to 70 km wide, depending on the sector.

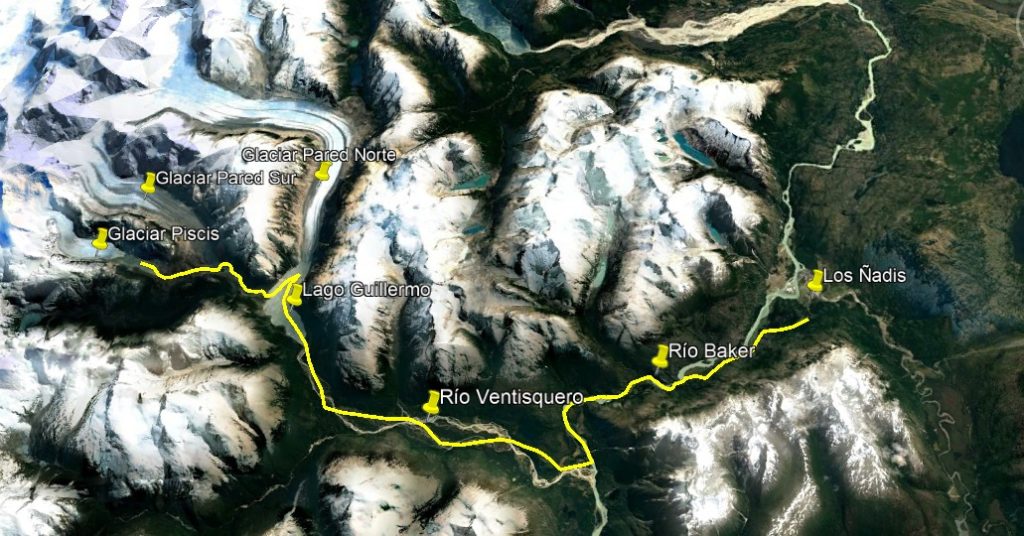

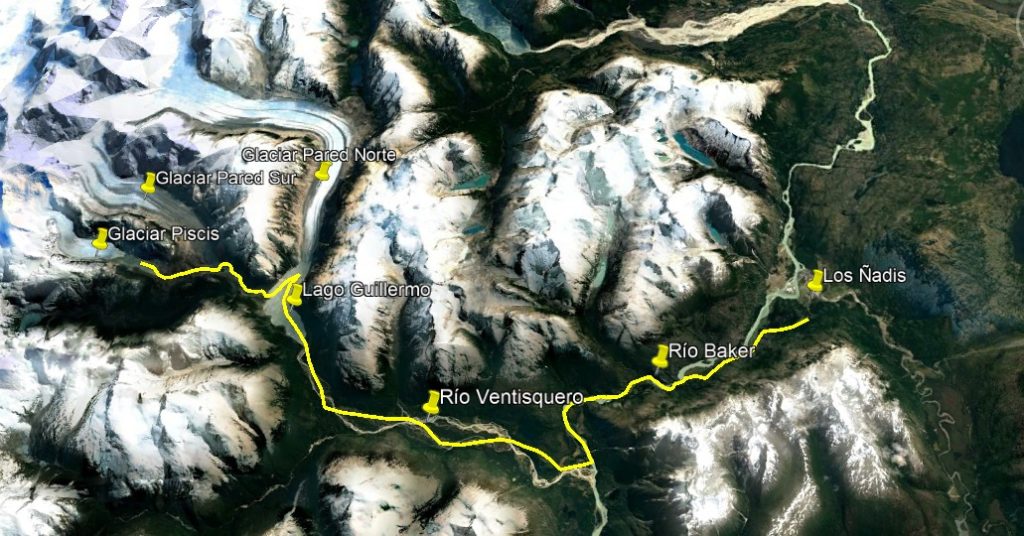

On my most recent expedition in October 2023, my partners and I went to the South-East sector of the Northern Ice Field. There, we explored the Piscis Glacier Zone, Pared Sur Glacier and Pared Norte Glacier, the latter being the largest in this sector.

Why this area?

Because in May 2023, my friends, Ignacio Sáez and Pablo Sanchéz, and I paddled over four days on the Baker River from the town of Cochrane to Caleta Tortel. Halfway through the route, we spotted the valley of the Ventisquero River that meets the Baker River. This valley marked the entrance to the Northern Ice Field. I had already seen this sector on the map some time ago. And I had dreamed of reaching all the possible glaciers of the Northern Ice Field via boat. At that moment, floating in my packraft at the confluence of the Ventisquero with the Baker, I thought it might be a good next destination to tick off my list.

I also chose this area because its glaciers and the ever-changing landscapes around them fascinate me. During the “Age of Man” (between the 14th & 19th Centuries) the planet experienced a mini ice age, where frontal moraines formed on the glaciers of Campo Hielo Norte (i.e. rocky material deposited by the same glacier in growth until reaching its peak). Records from the 1870s show these moraines forming on the Exploradores Glacier or the Grosse Glacier, both from Campo de Hielo Norte.

It’s a privilege for me to be able to paddle or walk to places that were covered in ice just 200 years ago, especially with technologically advanced equipment like packrafts, drysuits and UL gear! So while these aren’t exactly blank spots on the map, they are essentially unexplored. And I wanted to be the first in centuries to explore this area!

the northern icefields: the southeast sector

So I contacted Andres Mora and Jorge Diaz, who had already done similar expeditions to the San Quintin Glacier (the largest in Campo Hielo Norte) and the Gualas and Reitcher Route (which is the trip I am running with Four Corners Guide March 17-24). And we started planning this new adventure.

Los Ñadis

We would begin the expedition in the sector of Los Ñadis, south of the town of Cochrane. From Los Ñadis we would have to surmount the first natural barrier to reach the valley of the Ventisquero River and Lake Guillemo, the famous Baker River, the largest river in the country. In this area of the Baker basin lies the symbolic Paso San Carlos. Built at the beginning of the last century, settlers and pioneers used this path to travel and move their animals using “pilcheros” (loaded horses). It’s now considered historical heritage and one of the most emblematic routes of the Chilean Patagonia.

The San Carlos Pass

The San Carlos Pass is located between 26 to 107 meters above the Baker River (91 to 172 meters above sea level), in the undercut of a cliff about 590 meters high. It’s length reaches 644 meters long, on the south side of the riverbed. In those years, the Carretera Austral did not exist and the first settlers in the area opened this path. It’s an excellent example of how difficult it was to move around in Patagonia due to its complicated geography. Nowadays residents of Los Ñadis or Lily, the owner of the campsite, offer horseback riding to Paso San Carlos. Though a destination within the Carretera Austral that few people visit, I highly recommend it

Day 1: Los Ñadis - Río Ventisquero

The first day we started walking from a refuge in the Ñadis sector. We left the vehicle near Lily’s campsite and walked to the Baker River. Then we paddled to the confluence with the Ventisquero River. There, we found the house of Don Rene Muñoz, a settler of the area. He and his family are undoubtedly an important part of the history of the place. Unfortunately he was not at home. Don Rene Muños was also one of the activists in the Patagonia Sin Represas movement fighting against foreign companies planning to build dams on different rivers in southern Chile. We camped near his ranch. Rain and wind accompanied us the entire first day.

Day 2 and 3: Hiking through the Ventisquero Valley to Lago Guillermo

Bad Weather, Tough Going

The weather did not let up much. And low clouds obscured long views of the landscape. But we did experience a stunning, sweet-smelling evergreen forest in the non-stop fine rain that fell. From the first camp we started the hike with the intention of reaching Lago Guillermo, where the Ventisquero River is born. This is also where the front face of the Pared Norte Glacier descends. Little information is published about either the lake or glacier.

From Don Rene Muñoz’s ranch we took various animal tracks to get to Lake Guillermo. The settlers used these same tracks for decades to take their animals, mainly cows, up to the lake.

Talking with local people, we learned that it took them a full day on horseback to get to the lake. Walking with our backpacks and equipment it took us two days. We made more than a dozen river crossings. Inflate, deflate, repeat. It exhausted us to empty our heavy packs, and put everything back in moments later after making the crossing. Plus, with the river and the constant rain, most of our clothes and gear got soaked. We felt pretty disheartened.

Day 3: The Bomb!

Luckily, by the third day the weather improved. And after having camped in the middle of the route between the confluence of the Baker-Ventisquero and Lago Guillermo, we arrived at the lake in high spirits. How stunning the lake was! Bright sunshine lit up icebergs that littered its shores. Many were quit large, others blue or white, and several with what we call “dirty ice,” with layers of dirt and stone on its surface. Near the lake outlet, the shore has a pretty good beach for camping, ideal for a good rest and with the incredible view.

Day 4: Lake Guillermo

After the first intense days, this day’s mission would be mellow, or so we thought. We’d approach the front face of the Pared Norte Glacier and camp on the other side of the lake. There, we’d set up a base camp and leave the next day with smaller loads to the glacier sectors, Pared Sur and Glaciar Piscis (the farthest on the route of the expedition). From our camp at the lake outlet, we still could not see the North Wall Glacier.

Once in the iceberg-filled lake, we marveled at the tremendous 200- to 300-meter high cliffs on the side of the lake. These were covered by ice just 200 years ago! We paddled close to the front face of the glacier, at a safe distance as it had several ice detachments. The glacier descends from Campo de Hielo and has a curve. On the satellite map it almost looks like it has an L shape.

Our first evidence that it would not be a chill day…

Our first evidence that this day would give us more than we bargained did not take long to manifest. When we were about one kilometer from the glacier, we suddenly heard a roar. I thought it was a piece of glacier breaking off. As a packrafting guide, I see these all the time on Laguna San Rafael. But within seconds, we realized a landslide of rocky material was falling directly into the lake, where about 20 minutes ago we had paddled. It immediately caused a sequence of large waves that would hit us a few minutes later. This landslide was followed not long after by avalanches from the upper parts of the hill.

Adrenaline ran high. I felt very small in that moment. This region is very active, another reason it draws me. And I knew the decisions we’d make would be critical to our safety.

Reaching Basecamp Safely 😮💨

We made it safely to our next base camp, rested, dried our clothing and drank mate for the remainder of the beautiful afternoon. Experiencing close calls like we had on Lake Guillermo brought our team closer together. A year ago we were strangers. These days I trust them with my life. Jorge is a doctor and Andres was a merchant marine. That afternoon, they shared stories with me about their world travels.

Day 5: Pared Sur Glacier and Pisces

The walk in

After our afternoon of rest, we felt ready for our next day’s explorations. We left several kilos of weight behind so we could move faster. This would be one of the longest days of the expedition.

On the first stretch we walked along a river and the Laguna Ventisquero, which would be the pro glacier lagoon (lake formed by the retreat of the glacier) of the Pared Sur. We found traces of huemul or puma trails through the friendly terrain and easily covered a lot of ground. And with perfect weather conditions, it took us just two hours to reach a rocky scree field, which we at first thought was the front moraine of the Pared Sur Glacier.

However, it turned out to be a landslide from several years go. Trees had begun to grow in the scree! Walking suddenly became quite difficult. Loose stones would easily break an ankle and end our trip. So we focused, and after an hour finally saw the glacier. Its entire front face was so covered with dirty ice, it could easily be mistaken for dirt or stones. But thanks to the clear day we had a view of some of the mountains of the Ice Field: Serrucho, Cavagnetto and Cerro Pared Norte, among others.

backtracking out & exploring a second glacier

We returned along the same path and then headed to the river valley descending from Laguna Turbia and the Piscis Glacier. With noticeably better terrain conditions, though steeper conditions, we advanced more quickly. And after a couple of hours we arrived at the shores of the Turbia Lagoon.

The sun was high when we reached Pared Sur Hill and the Piscis Glacier, a place few have explored. Many consecutive warm days thawing the ice meant the lagoon and river ran a grayish-brown, colored by silt and detritus. It contrasted sharply with the turquoise front face of the glacier, which had much cleaner ice than the Pared Norte and Pared Sur glaciers. We found some great sandy camps along the shore of the Laguna Turbia and considered how nice it would be to camp among the blue icebergs. But we would be returning to base camp that night.

It took us from 8a.m. to 8p.m. to get back to camp, where we quickly ate dinner and fell into a deep sleep in our tents.

Day 6 & 7: Departing Lake Guillermo and descending the Ventisquero & Baker rivers

Paddling On Thin Ice

Waking to more good weather, we pondered our next step; crossing the lake to find the Ventisquero River. We knew we’d have to paddle past icebergs. But we didn’t expect the lake to be covered with a layer of ice. Worried our packrafts would puncture, we carefully paddled, as the blades cracked the ice. But we finally realized we could link together small stretches of clear pools to avoid most of it. Our calm paddle across the lake had turned into a painstaking mini epic.

Once off the lake, we walked about two kilometers to the start of the river. Though we could not see the river in its entirety from Google Earth, we knew it would have rapids due to the slope of the terrain and the images we had seen (Note: we’ll be reviewing these types of details with guests on the Patagonia trip in March!)

Class II+ Fun!

And almost immediately after starting the descent, we paddled dozens of very entertaining rapids, some of them quite strong, perhaps Class II+. What we had walked in the first days, we paddled down in a couple of hours. Fantastic day! We found fun wave trains, some holes that could be seen from far away and quite strong eddy lines. And we would have reached the confluence with the Baker River that night. But someone flipped and swam. Luckily, with our combined rescue skills we got him back in his boat without issues.

The next day we paddled about an hour, arriving to the Baker Dock, where we had access to the Carretera Austral. We hitchhiked to Los Ñadis, where we had left our vehicle at the beginning.

Summary: does the way you look at life change after a patagonia packraft expedition?

Over seven intense days we covered about 100 km between paddling and hiking in this relatively unknown and unexplored corner of Chilean Patagonia. People say that trips like these change the way you look at life. Personally, I feel immense gratitude. I always ask myself: “What have I done in this life to deserve this gift of adventure? And what can I do in return?”

First, I try to apply everything I have learned to my daily routine. How can I live with less? And how can I more fully enjoy each moment I am alive and share that with others!? Second, how can I be a better listener with and more respectful of my friends, family and co-workers like I am with my expedition partners? And, third, in what ways can I now share these learnings and experiences with others?

Well it so happens that I am now a writer and a guide who is sharing this article and other media with you! And this March I’m partnering with Four Corners Guides in order to share my love and knowledge of Patagonia with people who otherwise would not have the opportunity. Scroll to the bottom of the post for details.

Gualas & Reitcher Glaciers & Sur River Expedition Course with Four Corners Guides & Scouting Rios

As I mentioned earlier, Doom, Lizzy and I are offering our first Patagonia packraft expedition for folks from the USA, Canada or elsewhere through our two guide services: Four Corners Guides and Scouting Rios.

We chose this special route located in the North-West sector of the Northern Ice Field. Both glaciers fall into their respective pro-glacier lake. With similar terrain, the experience will be much like the most recent one I had. Obviously each glacier is different. And in this sector of the Ice Field, we are closer to the area of the fjords and channels of Patagonia. So the weather, rivers and mountains are different. But the way we travel is not. Undoubtedly, a boat like the packraft is a key tool to explore places like these in an environmentally-friendly, human-powered manner. We won’t adversely affect the landscapes we visit, treading on them lightly, as one might in the Southwest desert.

A classic patagonia packraft expedition route?

And maybe, just maybe, this trip will become one of the classic Patagonia packraft expeditions. Though that might take some time… Without marked trails, and using the traces of explorers who have already been there or tracks of wild animals, for now we will be advancing through mostly untouched terrain. The stretch from the end of Lake Reitcher to the source of the South River will be a pass through the dense evergreen forest of the Patagonian fjords, an alpine jungle.

And anyone who passes through here must be at least an intermediate boater, as the wild Sur River has different levels of rapids, depending on the level of water, from Class II to III+. The coolest thing about this area is it will always be a little different than it was the last time someone visited it. It’s a fast-moving, fast-changing young mountain range, with ever-changing glaciers, especially during these times of global warming. We invite you to join us in March to experience Patagonia’s glaciers this spring, 2024. There’s room for just eight people on the trip. You can find out more about it on the Patagonia Packraft Expedition Course registration page.